By Kamal Sikder

India perceives Sheikh Hasina’s potential defeat as a setback for the country, given the close alignment of the Indian government with her administration, which includes backing her actions amidst allegations of human rights violations. Since Sheikh Hasina took refuge in India following her ousting from power by the Bangladeshi populace, the Indian regime and its media have initiated a smear campaign against Bangladesh. A prominent example of this is the incitement of unrest among the tribal communities in Bangladesh’s northeast, particularly in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Reports suggest that the Kuki-Chin group, which is advocating for a separate state in India’s northeast, is allegedly receiving arms from India to destabilize the CHT region in Bangladesh thus exporting its unrest to Bangladesh to put pressure on the country’s interim government. Hasan Arif, the Adviser for Local Government, has attributed the current unrest in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) to the interference of a foreign power. He emphasized that in discussions with various stakeholders, there was a unanimous consensus that certain external miscreants are attempting to disrupt the harmony among the diverse communities in the region. According to Arif, this outside influence is exacerbating tensions and complicating the already fragile social fabric of the CHT, highlighting the need for vigilance against external actors who may be seeking to instigate discord for their own purposes.

Recent incident

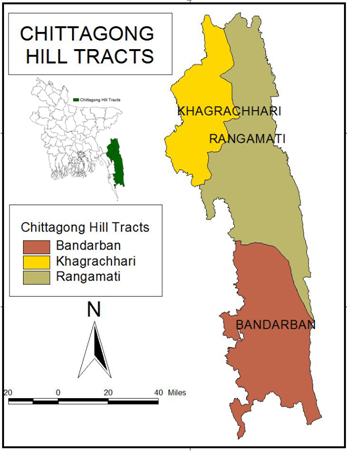

On September 18, a group of tribal individuals lynched a Bengali youth, accusing him of theft. This incident escalated ethnic tensions, leading to the destruction of homes and businesses on both sides. Currently, a 72-hour blockade of roads and waterways is being organized by student-led ethnic groups in the hill districts of Khagrachhari, Rangamati, and Bandarban, areas populated by various tribal groups. The protesters are demanding accountability for those responsible for the unrest, which intensified further on Thursday 21 September, resulting in the deaths of at least four men from ethnic minorities as well armed robbers killing a young Army Officer. The recent unrest in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) appears to be linked to the Bangladesh Army’s initiative to seize illegal arms that were reportedly looted from police stations during the unrest following Sheikh Hasina’s ousting. There is a growing concern that certain tribal factions, who may not want to surrender their weapons, instigated violence—such as the murder of a Bengali youth—to create instability in the region. This act of violence seems to be a tactic aimed at prompting the army to abandon its disarmament program.

This cycle of violence underscores the complex dynamics at play in the CHT, where external political pressures often exacerbate longstanding grievances related to ethnic identity, governance, and resource control. The conflict has not only highlighted the challenges faced by tribal communities but also the broader implications of political instability in Bangladesh. The situation remains precarious, with the potential for further violence if diplomatic solutions are not pursued effectively.

CHT is an integral part of Bangladesh

There is a consensus regarding the ownership of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Several tribal factions have long fought for self-determination following Bangladesh’s independence, stemming from misguided policies instituted by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The largest of these factions, the Chakma, initiated an armed rebellion against Bangladesh with support from India. In 1997, a peace agreement was reached between the Bangladeshi government and the Chakma’s armed group, Shanti Bahini, with India as the mediator. Nevertheless, despite the passage of 26 years, peace remains elusive in the Hill Tracts. Under Sheikh Hasina’s administration, a new insurgency arose among the Kuki-Chin group, demanding autonomy in their regions.

The tribal population are recent migrants to the region

The Chittagong Hill Tracts is home to 12 tribal groups, all of whom are relatively recent settlers, having migrated in the last 300 years. Collectively, these tribal groups represent merely 0.45% of Bangladesh’s population. They include the Chakma, Tripura, Marma, Um, Khumi, Chak, Khiyang, Lusai, Mro, Murong, Pangkho, Rakhain, Kuki, and Khasi. Historically, these groups have migrated from areas including Burma (Myanmar), India, and Thailand. Recently, some individuals in both Bangladesh and India have claimed that these groups are indigenous to the region, which contradicts historical documentation. It is important to note that individuals migrating from India and Myanmar cannot be classified as indigenous in the context of modern Bangladesh. Historically, the Bengali population inhabited the hilly regions long before the arrival of tribal communities, even though their numbers were comparatively lower than those in the plains. Archaeological findings from the Stone Age, such as “Stone Elements” (stone weapons) found in Rangamati and “Hand Axes” (tools) discovered in Feni, trace back 10,000 to 15,000 years, signifying the ancient presence of Bengali civilization in these areas.

The Government of Bangladesh, under the directive of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, issued a report on January 28, 2010, addressing efforts to label tribal communities as “indigenous.” The report emphasizes that there are 45 tribal groups in Bangladesh, and under the Constitution, Hill District Council Act, Regional Council Act, and the 1997 Peace Accord, they are designated as “tribes” and not “indigenous.” However, some leaders, intellectuals, and journalists are deliberately referring to them as indigenous, which the government sees as a problem. Former Government MPs, such as Asaduzzaman Noor and Rashed Khan Menon, were pushing for the use of the term ‘indigenous’ despite the official stance. Many hill people and tribal leaders, including those in groups like the United People’s Democratic Front (UPDF), reject the ‘indigenous’ label, preferring ‘tribal’ or ‘Jumma.’ Santu Larma, who signed the Peace Accord, has also used the term ‘indigenous,’ but even within his organization, some disagree. The controversy gained traction during the caretaker government of 2007 when Chakma Raja Debashish Roy became an advisor. Since then, NGOs, human rights groups, and foreign organizations, including the UNDP, have promoted the use of the term ‘indigenous.’ These groups have invested heavily in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and are pushing for tribal people to be recognized as indigenous, which could enable international intervention under the UN’s Indigenous Rights Charter. Geopolitical analysts like Dr. Mohammad Abdur Rob argued that this effort is part of a broader foreign-backed neo-colonial agenda, with some Christian missionary groups and NGOs attempting to designate these tribal communities as indigenous.

Significant research by prominent scholars and ethnologists, including RHS Hutchinson (1906), T.H. Lewin (1869), Amarendra Lal Khisa (1996), J. Jaffa (1989), and N. Ahmed (1959), has provided considerable evidence through their writings, research papers, theses, and reports that the tribes in Bangladesh do not constitute the original or indigenous inhabitants of the land. This reinforces the argument against recognizing these groups as indigenous within the context of Bangladesh’s historical demographic framework. The Bengali population settled in the region long before the tribal groups, although the numbers of these groups have grown significantly since the 1980s and 1990s, currently surpassing the combined population of all tribal communities.

Traditionally, the tribal population in the Chittagong Hill Tracts lived as hunter-gatherers until relatively recently. Their lifestyle began to shift with the arrival of Bengali settlers, prompting many to establish permanent residences. Some tribal individuals have benefited from various government initiatives, and many now reside in urban areas across Bangladesh for educational and employment opportunities. Increasingly, tribal people are adapting to urban lifestyles, often more so than many Bengalis. While some have converted to Christianity, many continue to practice their traditional nature-based religions.

Historically, the Chittagong Hill Tracts were not considered a distinct entity during the Muslim rule of Bengal. In 1861, the British administration separated the region from Chittagong for administrative purposes. During the Sultanate era, Chittagong served as a base for Rakhine and Portuguese pirates, who frequently raided Bengal. In 1340 CE, Sultan Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah led a military expedition that conquered Chittagong, defeating the pirates and driving them further into Burma.

Context of the tension

The issue of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) arose in the mid-1930s when certain tribal leaders, anticipating the partition of India, sought to detach the CHT from Bengal and integrate it into India. They reached out to Indian leaders such as Gandhi and members of the Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha. A delegation led by Congress leaders campaigned for the inclusion of the CHT in India, but these efforts ultimately failed. Consequently, in 1946, tribal chiefs formed the Hillmen Association, advocating for the transformation of the CHT into a princely state and the establishment of a confederation with neighbouring states under Indian governance. However, this proposal did not materialize either.

In 1947, during the partition, the Radcliffe Commission decided to include the CHT in Pakistan, despite opposition from some Indian leaders and local tribal chiefs. The Radcliffe Commission declined to incorporate the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) into India, citing significant security risks for the Chittagong port as a primary concern. This decision was made in the context of ensuring regional stability, as similar considerations had influenced the allocation of districts like Nadia, Murshidabad, and Malda to India, despite their predominantly Muslim populations. The rationale behind these allocations was to safeguard the security of the Kolkata port, illustrating the strategic importance of port security in the partition decisions. Thus, the exclusion of the CHT from Indian territory was rooted in a broader geopolitical strategy aimed at maintaining control and security in critical maritime areas. On August 14, 1947, pro-India Chakma leaders raised the Indian flag in Rangamati, expressing their hopes of joining India, but the CHT officially became part of Pakistan. Although some tribal leaders continued to resist this incorporation, Pakistani forces established full control over the region on August 21, 1947.

Following Pakistan’s independence, the CHT was designated as a “special region” in the 1956 and 1962 constitutions, but this status was revoked in 1963. Tribal leaders opposed this decision and continued to pursue autonomy. In the 1970s, under the leadership of Manabendra Narayan Larma, the Hill Students’ Association and other tribal organizations emerged. After Bangladesh’s independence, tribal leaders called for autonomy and the acknowledgment of their rights. However, Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman dismissed their demands, advising them to assimilate into Bengali nationalism, which led to increasing unrest.

In response, Larma established the Jana Samhati Samiti (JSS) in 1972, which later created an armed wing called “Shanti Bahini” to fight for autonomy. The conflict escalated in the 1980s, with internal divisions among tribal leaders exacerbating violence. In 1983, Larma was assassinated, and leadership passed to his brother, Santu Larma.

The conflict persisted into the 1990s, marked by intermittent peace talks and attempts to address tribal grievances. Ultimately, in 1997, the Bangladesh government, led by the Awami League, signed a peace agreement with the JSS, granting a degree of local autonomy to the CHT region and facilitating the disarmament of Shanti Bahini fighters. However, not all tribal groups accepted this agreement, and the region continues to be a complex and sensitive issue.

The crisis in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, which began shortly after Bangladesh’s independence, has significant implications due to alleged Indian involvement. The crisis primarily concerns the indigenous tribes of the CHT, especially the Chakma people, who have sought autonomy from the Bangladeshi government due to political, cultural, and land-rights concerns. The Shanti Bahini (SB), a militant faction of the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti (PCJSS), was established to advocate for indigenous rights and autonomy.

India’s Role in the Chittagong Hill Tracts Crisis

India’s involvement in the CHT crisis became apparent due to its geographic proximity, with many CHT refugees, particularly Chakmas, seeking asylum in neighbouring Indian states like Tripura and Mizoram. Reports indicate that India has provided refuge to Chakma insurgents, offering training, arms, and political support to the Shanti Bahini. Some accounts suggest that Indian authorities permitted the Shanti Bahini to establish bases within Indian territory, providing logistical backing to the insurgency. India’s support has been partly motivated by strategic interests, including exerting influence over Bangladesh and managing regional geopolitics, particularly concerning its northeastern tribal areas.

Despite its support for the CHT insurgency, India paradoxically suppresses separatist movements in its own northeastern states, such as Nagaland and Assam, which face similar cultural and political challenges as the CHT. India’s strategy seems to serve a dual purpose—applying pressure on Bangladesh while preventing any spillover effects on its own tribal populations.

Some analysts suggest that India aimed to leverage the CHT crisis to assert control over strategic assets in Bangladesh, particularly the Chittagong Port, a crucial maritime entry point in the region. The geographical significance of the CHT also places it at a strategic crossroads near Myanmar and China, enhancing its geopolitical importance.

In 1997, a peace accord was signed between the Bangladeshi government and the PCJSS, represented by Shanti Bahini leader Santu Larma. The agreement allowed for a certain degree of local autonomy for the CHT, along with the disarmament of Shanti Bahini fighters. While the accord brought a measure of peace to the region, it did not fully resolve underlying tensions, as many tribal groups felt excluded from the peace process. Moreover, sporadic violence and demands for further autonomy persisted, reflecting ongoing discontent among various factions.

Kuki-Chin National Front Situation in Bandarban

The Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF) has recently become a major topic of discussion in Bandarban, Bangladesh. Former Bangladeshi government led by Autocrat Sheikh Hasina labelled them as separatists, a claim that the KNF denies. The Bangladesh Army plays a significant role in maintaining security in the hilly regions. In response to inquiries from BBC Bangla about the current situation, the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) released a written statement indicating that regional armed groups are embroiled in conflicts over dominance and financial interests. These internal conflicts sometimes endanger ordinary citizens and law enforcement personnel. The Bangladesh Army is coordinating with local authorities and law enforcement to maintain regional peace and stability. The KNF claims to represent at least six ethnic groups in Bandarban and Rangamati, although some media portray them as primarily representing the Bawm ethnic group. Their military wing is known as the Kuki-Chin National Army (KNA).

Security analysts, such as retired Major Md. Emdadul Islam, express concern over the mystery surrounding the KNF’s acquisition of weapons and training, as well as their sudden involvement in violent conflicts. When the peace agreement was signed in 1997, smaller groups existed in the hills, but organizations like the Kuki-Chin did not gain significant attention, and their demands were unclear. However, these groups, particularly the Kuki-Chin, have recently become active. Their members are reportedly present in the Ruma area of Bandarban and also in India’s Mizoram. Conflicts in Bandarban and other hilly districts are not new. In November of 2022, a clash at the Tambru border resulted in the death of a Squadron Leader from the Military Defense Intelligence Directorate (DGFI), while an officer from the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) was injured. In March of the same year, four people were killed in gunfire in the Ruma area of Bandarban. Additionally, a month prior, four individuals, including a soldier, died in an attack by the JSS on a military patrol. Since October of the previous year, Bangladeshi authorities announced joint operations against militants and separatists in remote areas of Bandarban. Special operations began in the Ruma and Roangchhari regions, during which tourist access to these areas was restricted, a measure that remains in effect. Geopolitics, Extortion, and Power Struggles in the Hill Tracts In the hilly regions, various active groups are primarily engaged in power struggles and the distribution of extortion profits rather than ideological conflicts. These power dynamics frequently lead to violent clashes as factions vie for control.

Security analyst Major (Retd) Imdadul Islam states, “There isn’t much ideological conflict; the core issue revolves around power dynamics and extortion. I have observed that various groups collectively engage in extortion amounting to over 700 crore Taka annually. The quest for control over this rampant extortion is what fuels much of the violence.” He adds that the hill tracts have often been viewed by various parties as a buffer zone, which has resulted in different armed groups receiving support from various sectors and countries for geopolitical reasons. Political Dynamics and the Challenges in the Hill Tracts Some political leaders in the hills allege that the divisions and factional conflicts are backed by administrative support, while the administration blames local sub-group rivalries. Many have turned to armed violence in frustration over the failure to implement peace agreements. Numerous NGOs operate in the three hill districts, with people from various parts of the country settling there. Currently, the ratio of settlers to indigenous people is almost equal, leading to a strengthening of rights and interests from both sides, which has put indigenous groups in a corner. M Abul Kalam Azad, a journalist, highlights that the inability to properly implement the peace agreement has resulted in ongoing divisions and conflicts over land ownership, control of forests and natural resources, extortion, and influence in the area. The circumstances during the peace agreement are no longer present, making its effective implementation much more difficult now than it was then.

Various Factions and Groups in the Hills

In 1997, when the peace agreement was signed between the Bangladesh government and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samiti (PCJSS), the United People’s Democratic Front (UPDF) opposed this agreement. Many analysts suggest that certain factions did not want the implementation of this agreement, which aimed to restore peace in the hill areas.

Gautam Dewan, the president of the Parbatya Chattagram Citizens’ Committee, told BBC Bangla in an interview in 2023, “In reality, it has been observed that the government has not taken strong steps towards the implementation of the agreement. Therefore, the issues remain unresolved. Moreover, some elements are creating obstacles to the implementation of the agreement.” He added, “There have been various steps taken by certain quarters to ensure that peace is not established and that the Hill Tracts remain turbulent. In many cases, we see regional small factions displaying tendencies to create divisions.” However, he did not clarify who these elements are.

Security analyst Major (Retd) Imdadul Islam said, “We can see that there are groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts who cannot accept the establishment of peace; they believe that such peace would undermine their dominance in the region. This is why the Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF) was formed, which has now become a source of unrest,” he continued. In 2017, the UPDF split, giving rise to a new faction called UPDF-Democratic, while the JSS had previously split to form another faction known as JSS (MN Larma).

Conflicts among these four groups in the hilly areas have been ongoing, resulting in the deaths of over a hundred individuals in clashes over the past five years. Security analyst Major (Retd) Imdadul Islam also noted, “There has been some encouragement from certain quarters to position smaller groups against the JSS.”

Conclusion

Almost everyone working on issues related to the hill tracts agrees that the core problems are political in nature, requiring political solutions driven by government goodwill. However, if some parties benefit from the lack of resolution, the problems are likely to persist. Thus, it is crucial to identify who controls the dynamics in the hill regions, why they do so, and what benefits they derive in order to take effective action; otherwise, any effort may prove futile.

- Kamal Sikder is UK Data Scientist, Journalist, and TV Presenter.