Blindfolded, handcuffed, and dragged from his secret prison for the first time in eight years, Bangladeshi barrister Ahmad Bin Quasem held his breath, bracing for the worst. Expecting the sound of a cocked pistol, he was instead thrown from a car into a muddy ditch on the outskirts of Dhaka—alive, free, and completely unaware of the national upheaval that had led to his sudden release.

“It was the first time I breathed fresh air in eight years,” the 40-year-old Quasem told AFP. “I thought they were going to kill me.”

Hours earlier, Sheikh Hasina, the Prime Minister responsible for Quasem’s abduction and disappearance, had fled the country. Her departure on August 5 abruptly ended 15 years of autocratic rule, characterized by mass detentions and extrajudicial killings of political opponents.

But Quasem remained in the dark. He had spent his long imprisonment in the “House of Mirrors” (Aynaghar), a facility operated by military intelligence, where detainees were kept in complete isolation, seeing no one but their own reflections.

Throughout his confinement, Quasem was shackled in windowless solitary confinement, deprived of any news from the outside world. He and several others had been indicted by a war crimes tribunal, a process ostensibly intended to deliver justice for past atrocities but widely criticized as a tool for Hasina to eliminate her political rivals.

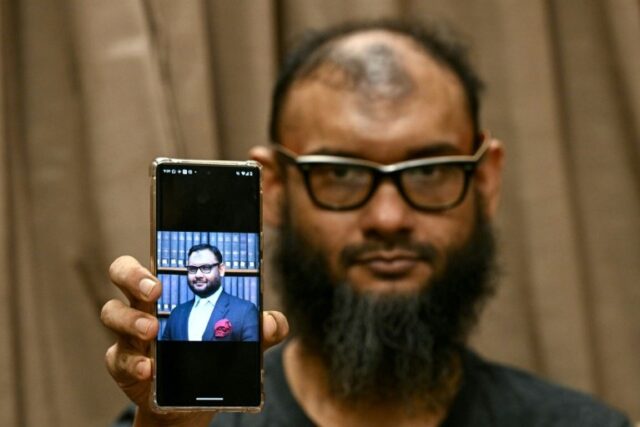

Whether Quasem’s father, whom he had been defending, was guilty or not was obscured by the travesty of justice that marked the tribunal proceedings. A London-trained barrister, Quasem had been 32 at the time, regularly briefing the media on the tribunal’s procedural flaws and judicial biases—criticisms echoed by rights groups and UN experts. These actions made him a target.

One night, plainclothes men stormed his home, snatching him from his family, dragging him down the stairs, and throwing him into a waiting car. “I never imagined they would disappear me just days before my father’s execution,” Quasem recalled. “I kept telling them, ‘Do you know who I am? I need to be there to conduct my case. I need to be with my family.’”

His father was hanged four weeks later, but Quasem only learned of it three years later when one of his jailers accidentally mentioned it.

After his release, Quasem walked through the night, trying to find his way home. By chance, he stumbled upon a medical clinic run by a charity his father had once supported. Recognized by a staff member, a phone number was quickly found, and his family rushed to be with him.

As the excited chatter around him filled him in on the student protests that had led to his release, Quasem was struck by the power of youth. “This entire thing was made possible by a few teenagers,” he said. “When I see these kids leading the way, I am really hopeful that this could be the moment where Bangladesh finds a new direction.”

Though Quasem and his family welcomed AFP into their home, the trauma of his detention was evident. The thick hair he once had was now reduced to a few wild tufts, and he had lost a significant amount of weight. His wife, Tahmina Akhter, spoke of the isolation she felt due to the publicity surrounding Quasem’s case, which led to social ostracism at their children’s school. Every year on the anniversary of his disappearance, the family was harassed and warned to stop drawing attention to it.

Quasem’s two daughters were just three and four years old when he was taken. The elder, who witnessed his abduction, remains fearful of certain authority figures, like the private security guard at her school. The younger didn’t remember him at all.

“For us, it didn’t feel like eight years,” said Quasem’s mother, Ayesha Khatoon. “It felt like eight lifetimes.”

Source: AFP